by ELMARIE

“My brother, I am a constant reader of my Bible, and I soon found that what I was taught to believe did not always agree with what my Bible said. I came to see that I must either part company with John Darby, or my precious Bible, and I chose to cling to my Bible and part from Mr. Darby.” George Müeller (1805–1898)

I am quite convinced that all the promises to Israél are found, are finding and will find their perfect fulfilment in the Church. It is true that in time past, in my expositions, I gave a definite place to Israél in the purposes of God. I have now come to the conviction, as I have just said, that it is, the new and spiritual Israél that is intended. G. Campbell Morgan (1863-1945)

Dispensationalism is a device of the enemy, designed to rob the children of no small part of that bread which their heavenly Father has provided for their souls; a device wherein the wily serpent appears as an angel of light, feigning to “make the Bible a new book” by simplifying much in it which perplexes the spiritually unlearned. It is sad to see how widely successful the devil has been by means of this subtle innovation. A. W. Pink(1886-1952)

It is mortifying to remember that I not only held and taught these novelties myself, but that I even enjoyed a complacent sense of superiority because thereof, and regarded with feelings of pity and contempt those who had not received the “new light” and were unacquainted with this up-to-date method of “rightly dividing the word of truth.” For I fully believed what an advertising circular says in presenting “Twelve Reasons why you should use THE SCOFIELD REFERENCE BIBLE,” namely, that: “First, the Scofield Bible outlines the Scriptures from the standpoint of DISPENSATIONAL TRUTH, and there can be no adequate understanding or rightly dividing of the Word of God except from the standpoint of dispensational truth.”

What a slur is this upon the spiritual understanding of the ten thousands of men, “mighty in the Scriptures,” whom God gave as teachers to His people during all the Christian centuries before “dispensational truth” (or dispensational error), was discovered! And what an affront to the thousands of men of God of our own day, workmen that need not to be ashamed, who have never accepted the newly invented system! Yet I was among those who eagerly embraced it (upon human authority solely, for there is none other) and who earnestly pressed it upon my fellow Christians. I am deeply thankful, however, that the time came (it was just ten years ago) when the inconsistencies and self contradictions of the system itself, and above all, the impossibility of reconciling its main positions with the plain statements of the Word of God, became so glaringly evident that I could not do otherwise than renounce it. Philip Mauro (1859-1952)

Jesus answered and said unto them,

“Ye do err, not knowing the scriptures, nor the power of God.”

Matthew 22:29

The History of Dispensationalism

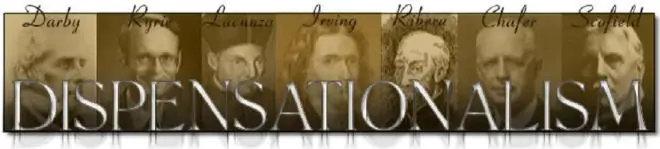

Dispensationalism is a method of Bible interpretation which was first devised by John Nelson Darby (1800-1882), and later formulated by the controversial American Cyrus Ingerson Scofield [sometimes referred to as CyrusIngersoll Scofield] (1843-1921), and is also known as Pre-millennial Dispensationalism. Although Darby was not the first person to suggest such a theory, he was, however, the first to develop it as a system of Bible interpretation and is, therefore, regarded as the Father of Dispensationalism.

The origin of this theory can be traced to three Jesuit priests; (1) Francisco Ribera (1537-1591), (2) Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) one of the best known Jesuit apologists, who promoted similar theories to Ribera in his published work between 1581 and 1593 entitled Polemic Lectures Concerning the Disputed Points of the Christian Belief Against the Heretics of This Time, and (3) Manuel Lacunza (1731–1801). The writings of Ribera and Bellarmine, which contain the precedence upon which the theory of Dispensationalism is founded, were originally written to counteract the Protestant reformers’ interpretation of the Book of the Revelation which, according to the reformers, exposed the Pope as Antichrist and the Roman Catholic Church as the whore of Babylon.

Ribera’s theory lay dormant until it was revisited by Lacunza, and Lacunza’s work the Coming of Messiah in Glory and Majesty (Vol.I, Vol.II.), was translated into English by Edward Irving (1792–1834) in 1827. However, Irving was not aware that the author of this work was not the converted Jewish Rabbi he pretended to be, but a Roman Catholic imposter, and a Jesuit at that! Irving was duped into believing that Lacunza was a converted Jewish Rabbi named Juan Josafat Ben-Ezra, and he was taken in by his anti-Protestant writings. It should be noted that J. N. Darby was also vehemently opposed to Protestantism and at one time, like his friend John Henry Newman, considered converting from Anglicanism to the Roman Church. Having been led astray by this Jesuit work, Irving completely rejected the historical orthodox Christian belief concerning the return of Jesus Christ; as the following extract from his introduction to his translation of Lacunza’s work clearly shows.

“…having, by God’s especial providence, been brought to the knowledge of a book, written in the Spanish tongue, which clearly sets forth, and demonstrates from Holy Scripture, the erroneousness of the opinion, almost universally entertained amongst us, that He is not to come till the end of the millennium, and what you call the last day, meaning thereby the instant or very small period preceding the conflagration and annihilation of this earth; I have thought it my duty to translate the same into the English tongue for your sake, that you may be able to disabuse yourselves of that great error, which hath become the inlet to many false hopes, and will, I fear, if not speedily corrected, prove the inlet to many worldly principles and confederacies, and hasten the ruin and downfall of the present churches.”

Another Roman Catholic counter-interpretation to that held by Protestants is that of Luis De Alcazar (1554-1613), a Spanish Jesuit. Alcazar also wrote a commentary on the book of the Revelation entitled An Investigation into the Hidden Meaning of the Apocalypse. In which he suggests that the entire Revelation applies to pagan Rome and the first six centuries of Christianity. Perhaps the Roman Catholic origin of the dispensationalist view is best described by Le Roy Edwin Froom.

It was Irving’s own interest in prophecy which led him to the works of Manuel Lacunza, (who wrote using the false Jewish name of Juan Josafat Ben-Ezra). Lacunza’s ideas were similar and probably based on the writings of the sixteenth century Jesuit, Francesco Ribera. Ribera was one of the Jesuits commissioned by the Pope to write a commentary on the book of Revelation that would hopefully counteract the anti-Catholic Protestant interpretation held at that time.

In 1590, Ribera published a commentary on the Revelation as a counter-interpretation to the prevailing view among Protestants which identified the Papacy with the Antichrist. Ribera applied all of Revelation but the earliest chapters to the end time rather than to the history of the Church. Antichrist would be a single evil person who would be received by the Jews and would rebuild Jerusalem.

George Eldon Ladd. The Blessed Hope: A Biblical Study of the Second Advent and the Rapture. 1956. pp. 37-38.

Ribera denied the Protestant Scriptural Antichrist (II Thessalonians 2) as seated in the church of God—asserted by Augustine, Jerome, Luther and many reformers. He set on an infidel Antichrist, outside the church of God.”

Ralph Thompson. Champions of Christianity in Search of Truth. p. 89.

The result of his work [Ribera’s] was a twisting and maligning of prophetic truth.

Robert Caringol. Seventy Weeks: The Historical Alternative. p. 32.

At the Council of Trent the Jesuits were commissioned by the Pope to develop a new interpretation of Scripture that would counteract the Protestant application of the Bible’s Antichrist prophecies to the Roman Catholic Church. Francisco Ribera (1537-1591), a brilliant Jesuit priest and doctor of theology from Spain, basically said, “Here am I, send me.” Like Martin Luther, Francisco Ribera also read by candlelight the prophecies about the Antichrist, the little horn, that man of sin, and the Beast.

But because of his dedication and allegiance to the Pope, he came to conclusions vastly different from those of the Protestants. “Why, these prophecies don’t apply to the Catholic Church at all!” Ribera said. Then to whom do they apply? Ribera proclaimed, “To only one sinister man who will rise up at the end of time!” “Fantastic!” was the reply from Rome, and this viewpoint was quickly adopted as the official Roman Catholic position on the Antichrist.

“In 1590, Ribera published a commentary on the Revelation as a counter-interpretation to the prevailing view among Protestants which identified the Papacy with the Antichrist. Ribera applied all of Revelation but the earliest chapters to the end time rather than to the history of the Church. Antichrist would be a single evil person who would be received by the Jews and would rebuild Jerusalem.” “Ribera denied the Protestant Scriptural Antichrist (2 Thessalonians 2) as seated in the church of God—asserted by Augustine, Jerome, Luther and many reformers. He set on an infidel Antichrist, outside the church of God.” “The result of his work [Ribera’s] was a twisting and maligning of prophetic truth.”

Following close behind Francisco Ribera was another brilliant Jesuit scholar, Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) of Rome. Between 1581 and 1593, Cardinal Bellarmine published his “Polemic Lectures Concerning the Disputed Points of the Christian Belief Against the Heretics of This Time.” In these lectures, he agreed with Ribera. “The futurist teachings of Ribera were further popularized by an Italian cardinal and the most renowned of all Jesuit controversialists. His writings claimed that Paul, Daniel, and John had nothing whatsoever to say about the Papal power. The futurists’ school won general acceptance among Catholics. They were taught that Antichrist was a single individual who would not rule until the very end of time.” Through the work of these two tricky Jesuit scholars, we might say that a brand new baby was born into the world. Protestant historians have given this baby a name—Jesuit Futurism. In fact, Francisco Ribera has been called the Father of Futurism.

Steve Wohlberg. Left Behind by Jesuits.

So great a hold did the conviction that the Papacy was the Antichrist gain upon the minds of men (who held the historicist view), that Rome at last saw she must bestir herself, and try, by putting forth other systems of interpretation, to counteract the identification of the Papacy with the Antichrist.

Accordingly, toward the close of the century of the Reformation, two of the most learned (Jesuit) doctors set themselves to the task, each endeavouring by different means to accomplish the same end, namely, that of diverting men’s minds from perceiving the fulfilment of the prophecies of the Antichrist in the papal system. The Jesuit Alcazar devoted himself to bring into prominence the preterist method of interpretation,…and thus endeavoured to show that the prophecies of Antichrist were fulfilled before the popes ever ruled in Rome, and therefore could not apply to the Papacy.

On the other hand, the Jesuit Ribera tried to set aside the application of these prophecies to the papal power by bringing out the futurist system, which asserts that these prophecies refer properly, not to the career of the Papacy, but to some future supernatural individual, who is yet to appear, and continue in power for three and a half years. Thus, as Alford says, the Jesuit Ribera, about A.D. 1580, may be regarded as the founder of the futurist system of modern times.

…It is a matter for deep regret that those who advocate the futurist system at the present day, Protestants as they are for the most part, are really playing into the hands of Rome, and helping to screen the Papacy from detection as the Antichrist.

Rev. Joseph Tanner. Daniel and the Revelation. pp. 16-17.

Edward Irving’s prophetic views were themselves based largely on the theories of these Jesuit writers, especially upon their commentaries on The Revelation. This combined with the ideas of his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)**, appear to be the basis of Irving’s millennialism.

“Probably the religious opinions of Irving, originally in some respects more catholic and truer to human nature than generally prevailed in ecclesiastical circles, had gained breadth and comprehensiveness from his intercourse with Coleridge, but gradually his chief interest in Coleridge’s philosophy centred round that which was mystical and obscure, and to it in all likelihood may be traced his initiation into the doctrine of millenarianism….it was through Irving that Lacunza’s theory was introduced to the early leaders of the Plymouth Brethren whose early leaders such as John Nelson Darby attended one of the conferences on biblical prophecy at Powerscourt House (the home of Lady Powerscourt) and various other localities in County Wicklow from 1830 to 1840.”

Irving got his interpretation of the book of The Revelation from Jesuit priests who had deliberately set out to lie and deceive by placing the events foretold in Revelation in some future scenario, and this in an attempt to hide the truth and avoid any connection between the Biblical Antichrist and the Pope of Romanism.

It is important also to note that Irving was also influenced by his friend Henry Drummond. The subject of “unfulfilled prophecy” was the main topic of interest and study at Drummond’s Albury Conferences, and particularly the study of Old Testament prophecy in relation to the book of The Revelation. It was at these gatherings that the concept of God’s unfulfilled promises to the Jews began to formulate.

It was Irving’s obsession with prophecy and his apparent misuse of the gifts of the Spirit, which lead to his excommunication from the Church of Scotland in 1830. His book on the Humanity of Jesus Christ caused a great deal of offence to church leaders. It was this book that led to him being declared unfit to remain a minister of the Church of Scotland. In 1832, after his dismissal from his ministerial position, Irving founded his own church – the Holy Catholic Apostolic Church. In March 1833 he was deposed from the ministry of the Church of Scotland on the charge of heresy. Irving died the following year.

Concerning the Brethren understanding of the person of Jesus Christ, F. F. Bruce says that there are “imbalances that need to be corrected in Brethren tradition,” and traces the problem directly to Irving himself.

“..a weakness on the doctrine of our Lord’s humanity, verging at times on Docetism, has been endemic in certain phases of the Brethren movement. The reason for this is that, almost at the outset of the movement, Brethren found themselves involved in debates on the Person of Christ of a kind which, more especially among the rank and file, caused any emphasis on His normal manhood to be almost suspect.

The trouble, I think, really goes back to Edward Irving (1792-1834). Irving, who was a leading participant in the Albury Park conferences (1826-30) and visited Lady Powerscourt at Powerscourt Castle in September 1830, published in the latter year his work on The Orthodox and Catholic Doctrine of our Lord’s Human Nature, in which he promulgated views which he had already ventilated in his preaching, and which led, three years later, to his conviction for heresy by the Presbytery of Annan and his expulsion from the ministry of the Church of Scotland.”

Whether Irving’s dismissal from the ministry prompted Darby to separate from the Church of Ireland the same year is not clear, but it was during the 1832 Powerscourt Conference held in Co. Wicklow, that he first described his discovery of a “secret rapture.” According to several authorities the concept of a secret rapture was the substance of a prophecy given by a girl belonging to one of Irving’s groups.

“The rise in belief in the “Pre-Tribulation” rapture is sometimes attributed to a 15-year old Scottish-Irish girl named Margaret MacDonald (a follower of Edward Irving), who in 1830 had a vision that was later published in 1861.”

However, a study of the published prophecy does not give this impression. Rather, the message conveys the need for the Lord’s people to be ready for His return by living in holiness and the fullness of the Spirit. There is NO reference whatever to a secret rapture.

It was the Jesuit Ribera who first taught that the events prophesied in the books of Daniel and Revelation would not be fulfilled until the final three and a half years of this present age. At that time, according to Ribera, anti-Christ would arise. Of course this position was a smoke screen to deflect from the fact that the Roman Catholic theologians knew clearly that the person depicted as anti-Christ in Scripture was none other than the Papacy. Ribera laid the foundation of a system of prophetic interpretation of which the Secret Rapture became an integral part.

However, despite of the efforts of Jesuits like Ribera and others, It took another two and a half centuries before this Jesuit deception was accepted within the walls Evangelical Churches.

In the early 19th Century Futurism entered the bloodstream of Protestant prophetic teaching by three main roads:

(i) A Chilean Jesuit priest, Emmanuel Lacunza wrote a book entitled ‘The Coming of Messiah in Glory and Majesty’, and in its pages taught the novel notion that Christ returns not once, but twice, and at the ‘first stage’ of His return He ‘raptures’ His Church so they can escape the reign of the ‘future antichrist’. In order to avoid any taint of Romanism, Lacunza published his book under the assumed name of Rabbi Ben Ezra, a supposedly converted Jew. Lacunza’s book found its way to the library of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and there in 1826 Dr Maitland, the Archbishop’s librarian came upon it and read it and soon after began to issue a series of pamphlets giving the Jesuit, Futurist view of prophecy. The idea soon found acceptance in the Anglo-Catholic Ritualist movement in the National Church of England, and soon it tainted the very heart of Protestantism.

(ii) The Secret Rapture doctrine was given a second door of entrance at this time by the ministry of one, Edward Irving, founder of the so-called ‘Catholic Apostolic Church’. It was in Irving’s London church, in 1830, that a young girl named Margaret McDonald gave an ecstatic prophecy in which she claimed there would be a special secret coming of the Lord to ‘rapture’ those awaiting His return. From then until his death in 1834 Irving devoted his considerable talent as a preacher to spreading the theory of the ‘secret rapture’.

(iii) However, it was necessary for Jesuitry to have a third door of entrance to the Reformed fold and this they gained via a sincere Christian, J. N. Darby, generally regarded as the founder of the ‘Brethren’. As an Anglican curate Darby attended a number of mysteriously organised meetings on Bible Prophecy at Powerscourt in Ireland, and at these gatherings he learned about the ‘secret rapture’. He carried the teaching into the Brethren and hence into the heart of Evangelicalism. With a new veneer of being scriptural the teaching spread and was later popularised in the notes of the Schofield Reference Bible.

Alan Campbell. The Secret Rapture. Is it Scriptural?

J. N. Darby, influenced by Edward Irving and followed by C. I. Scofield and the early dispensationalists such as Lewis S. Chafer and Charles Ryrie, held to this position. Ryrie describes pre-tribulationism as ‘normative dispensational eschatology’ and ‘a regular feature of classic dispensational premillennialism’. Pre-tribulationist premillennialists believe that Jesus Christ will return in the air to secretly ‘rapture’ true believers before the Tribulation begins on earth. After seven years of tribulation, Christ will return with His saints to overcome the Antichrist and his forces and establish God’s millennial kingdom on earth.

Stephen Sizer. Dispensationalism Defined Historically. 1997.

Although Arnold Dallimore, in his biography of Irving (The Life of Edward Irving. Banner of Truth Trust. 1983), makes no reference to Darby’s direct association with Irving, one of Darby’s biographers does. William Kelly, in referring to his and Darby’s companions says, “For in brighter days did not Edward Irving call it a “swamp of love”, when his own mind was carried away by pretensions to miraculous power, and to a ritual beyond the Ritualists?” F. F. Bruce also links Irving to Darby through Lady Powerscourt. Irving was a “leading participant in the Albury Park conferences (1826-30) and visited Lady Powerscourt at Powerscourt Castle in September 1830”, the same year as he published his work on The Orthodoxand Catholic Doctrine of our Lord’s Human Nature. [Bruce. op. cit.]. Darby attended at least one of the conferences on prophecy held at Powerscourt Castle and may well have met Irving there at the time. Another biographer, Max S. Weremchuk, who we will now quote from extensively, refers to Darby actually quoting Irving in his own writings.

“When Darby and Newton first met they went through Matthew 24 together and could not make head nor tail of it. Darby’s earliest papers, also those dealing with prophecy (in which he also quotes from Irving) do not support any pre-trib rapture views. …Of course he could have heard and read many things before his accident, he could have heard from Richard Graves’ views through Joseph Singer (with whom he had contact after returning to Ireland in the 1820s), he could have read Irving (he certainly did later) and others, but they do not appear to have affected him much at the time. I still feel his final Church/Israel distinction and pre-trib rapture views were a reaction, a sought for alternative, almost as if he tried to be “original”.”

Max S. Weremchuk. J. N. Darby.

Joseph Wolff, an associate of Darby’s, may have introduced him to Irving. In H. P. Palmer’s biography of Wolff we read the following,

“He reached Dublin harbour in May 1826. . .When Wolff was safely landed in Dublin, he soon found himself the guest of eminent people, as we are told that, after speaking at the Rotunda, ‘he spent some days with Lord Roden and the Archbishop of Tuam.’. . .After Wolff had spent some weeks in Dublin, his activities were cut short by an invitation from Henry Drummond and Edward Irving, the founder of the ‘Catholic and Apostolic Church,’ to come to London. Darby was of course a curate in Calary at this time. He knew the Rotunda meeting place (at the very least because of the Bible Society and Rev. Robert Daly) and Lord Roden (Jocelyn – related to the Wingfield/Powerscourt family) and Archbishop Trench. Did Darby meet Wolff at this time? Possibly. Given the circumstances and people involved I’d be quite inclined to think so. Was he given a further nudge as to his own prophetic views at the time? Madden in “Memoir of the Right Rev. Robert Daly, D.D.” writes, “An interesting account is given in the Memoir of the Rev. Edward Irving of some meetings which were held in the year 1826, at Albury, the seat of Henry Drummond, Esq.”

Lady Powerscourt was present at these meetings, as appears from a letter to Mr. Daly, of which the following is an extract: – ‘I am going to the prophets’ meeting at Mr. Drummond’s. . .” (pp. 142-144)

In 1834 Wolff “travelled in Great Britain and Ireland on behalf of the London Society in company with its secretary. Never was there a more ill-matched pair. Wolff was always determined to speak about the Millennium and the restoration of the Jews, while the secretary maintained that he should devote his attention to the doctrine of the justification by faith. The ladies at Carisle who supported the Society sent a request to Wolff through the secretary that he should speak on the latter subject only. Wolff proved adamant. ‘If I come,’ he said, ‘I shall want to convert them to my views, not that they should convert me to theirs.’ ” (p. 192).

Weremchuk. op. cit.

It should be noted here that Wolff was at one time A Roman Catholic and that Darby had several Roman Catholic acquaintances, like John Henry Newman (later Cardinal Newman) and Charles Butler (see below). This same author clearly connects Darby with Catholicism and this helps us understand Darby’s acceptance of Roman Catholic literature and teachings.

A possible Catholic influence on Darby could have been the Roman Catholic barrister Charles Butler (1750-1832) – whom Maitland apparently greatly admired. Below is information I was sent in connection with my inquiries regarding him: “Butler, who was half-French (and fully conversant with Continental Catholic thought), was lay Secretary of the Catholic Committee in England and Wales from 1786 until the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829. In 1831, shortly before his death, he was made a King’s Counsel (an office which had been denied him by law until the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act) and a bencher of Lincoln’s Inn, to which he had been admitted in 1775. For most of his career he practised as a conveyancer (that being the highest legal to which he could aspire as a Catholic) and was reckoned to be the finest such practitioner for much of his career. Butler was also steeped in the Scriptures and published on the subject. One of his kinsmen was Charles Plowden (1743-1821), Provincial Superior of the English Jesuits from 1817-1821. Though Plowden was based at the Jesuits’ headquarters at Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, he was regularly in London, visiting Fr Edward Scott, SJ (1776-1836), the London agent of Stonyhurst College from 1817-1832, and Plowden could well have met Darby on a visit to Butler. Certainly, Darby seems to have been heavily influenced by Jesuit literature on pre-trib. rapture and these influences could have come via Butler and Plowden and/or Scott.”

Weremchuk. op. cit.

B. W. Newton was convinced that J. N. Darby was working for the Jesuits. He says, “I often think he was in the employ of Jesuits; his brother was a Catholic and he himself at one time was known to be on the verge of joining just before he left the Bar.” (Fry MSS. Vol IV. pp. p. 44-45). Certainly Darby leant strongly to Roman Catholicism at one time and was well versed in Roman Catholic literature, especially that of Jesuits. He says of that time,

“I looked for the church. Not having peace in my soul, nor knowing yet where peace is, I too, governed by a morbid imagination, thought much of Rome, and its professed sanctity, and catholicity, and antiquity – not of the possession of divine truth and of Christ myself. Protestantism met none of these feelings, and I was rather a bore to my clergyman by acting on the rubrics. I looked out for something more like reverend antiquity. I was really much in Dr. Newman’s state of mind.”

Weremchuk. op. cit.

Weremchuk continues,

The Catholic influence may go further than suspected. Who did Darby converse with during his Catholic phase? How much teaching did he hear? These questions become important for the development of Darby’s prophetic views later. There are very many Catholic (Jesuit) elements involved in it. Darby’s view is not Ribera’s, nor Bellarmine’s, or Lacunza’s, but there are just too many corresponding elements when compared with each other that “chance” does not seem to be an honest explanation.

All the “elements” were there in the 1820s and 1830s: the concept of ruin, of dispensations, of a Israel/Church distinction, of a rapture (even though only a 45 day gap, but nevertheless, a gap), the days as days and not years in Daniel – and so on. It was all there. Darby just brought it all together in a way that seemed to be right.

Weremchuk op. cit.

Through the espousal of Jesuit Futurism by J. N. Darby and his followers, some one thousand five-hundred years of orthodox Christian prophetic history was discarded. Rome wants everybody to believe that the interpretation placed on Bible prophecy concerning anti-Christ has nothing whatever to do with the Roman Church. The Papacy wants us to believe that when Rome fell prophetic fulfilment halted, and will continue to be fulfilled from the time of the supposed Rapture.

Thus the “ten horns,” the “little horn,” the Leopard-like “Beast,” and the Antichrist have nothing to do with Christians today. According to this viewpoint no prophecies were fulfilled during the Dark Ages. This remained a Catholic view for some 300 years after the Council of Trent. The plan of the Jesuits was that the Protestants would adopt this idea one day. To their delight it happened in the early 1800s in England, and from there it spread to America.”

Concerning this false Jesuit teaching entering the Christian Church, Edgar F. Parkyns, says:

J. N. Darby and the Plymouth Brethren were amongst the early Protestant exponents of this view. Their literal interpretation of Bible prophecy and their ideas on the timing of the rapture and the Lord’s Second Coming attracted them to this futurist system of interpretation.

In the early 19th. century there was a great spiritual vacuum in Britain and America. …people like J. N. Darby, Edward Irving and others also found in that spiritually starved generation a ready audience for their futuristic ideas. Ribera’s cunning has had its fruit in the publication of lots of extraordinary literature.

Edgar F. Parkyns. His Waiting Bride. 1996. pp. 31-31

There can be very little doubt indeed that it was the teachings of Ribera and other Jesuits, through the influence of Irving and others of Darby’s friends, that led to Darby’s acceptance of the futurist interpretation of prophecy. When Darby first announced his conversion to these Jesuit teachings it brought immense opposition from within the movement he had helped to found, namely, the Brethren. His views also caused insurmountable theological problems for himself and for those who sided with him. He considered all those who would not acknowledge his adopted beliefs to be apostate, and he refused to fellowship with people who, up to that time, were his close Christian friends. This division resulted in a massive rift amongst the Plymouth Brethren and the founding of the Exclusive Brethren sect (Darby’s own followers).

It appears that John Nelson Darby had no theological training, but came to his personal views after many years of struggle.

Darby struggled with the claims of the Law for seven years, but he also struggled with the claims of the Church. His High Churchmanship is evidence of that. The demands he felt this placed on him almost drove him to despair and he sought an outlet for his conscience through the way he practised his “religion” at the time…

His realising himself to be one in Christ brought real deliverance. But was not the resulting emphasis on the “spiritual” an escape hatch? Could not now all elements dealing with tradition and ritual – which had troubled him so much – be ignored and conveniently pushed into the sphere of “earthly Israel”?

Why were others who worked with Darby during his time as a clergyman not driven by the same despair as he? Why did they continue on? And that with obvious success and blessing?

Was not Darby’s “solution” a very personal one? One he then applied to the Church at large? Not as a possibility, but as a demand!…

Darby struggled many years to come to a conclusion which finally brought him peace. But then he went and made this a requirement of all other believers! This became the standard he used to judge the “true” spirituality and devotedness of other Christians!

Weremchuk. op. cit.

When we look at the way Darby worked out his Dispensational theories, it is little wonder that anyone but the ignorant and gullibly could believe such things. This is how one of Darby’s associates, B. W. Newton, explains the matter.

When Darby came on the scene, in my first interview I asked him “Do you preach the Gospel to sinners as sinners and not merely as something for the elect?” And his answer satisfied me. For some while after I had met DeBurgh’s book on prophetic subjects, I lost sight of Darby: he was in Ireland. But when he came back I asked him about the Immediate Coming, and he would not decide either way. I argued with him that it couldn’t possibly be sinful to hope for the Lord’s return in the way that evidently Paul hoped for it — namely with intervening events — He wouldn’t decide.

Two years passed, and he wrote from Ireland saying that he had a scheme of interpretation now which would explain everything and bring all into harmony. And he would tell what it was when he came. When we met I inquired, and it was this elimination of all that could be considered Jewish. I warmly remonstrated.

At last Darby wrote from Cork saying he had discovered a method of reconciling the whole dispute, and would tell us when he came. When he did, it turned out to be the “Jewish interpretation.” The Gospel of Matthew was not teaching Church-Truth but Kingdom-Truth and so on. He explained it to me and I said “Darby, if you admit that distinction you virtually give up Christianity.” Well they kept on at that until they worked out the result as we know it. The “Secret Rapture” was bad enough but this was worse.

ibid.

As we have seen, Dispensationalism can be traced back to J. N. Darby, but it did not necessary originate with him. Darby borrowed from others and even plagiarised their ideas to formulated his Dispensation theory.

What is becoming more and more evident to me is that Darby had the tendency to present things as new (and sometimes as ‘his’) years after they had been presented by others. I have more examples of this from the field of prophecy, but apparently it is also the case in ecclesiastical matters.

For example, it is quiet odd to read Darby saying

“I am afraid, that many a cherished feeling, dear to the children of God, has been shocked this evening; I mean, their hope that the gospel will spread itself over the whole earth during the actual dispensation.” “As the Jewish dispensation was cut off, the Christian dispensation will be also.”

in 1840 when back in 1825/26 Irving and after that many others were preaching and writing about the Lord’s soon coming to judge the Church and restore Israel. The idea that began to become popular back then was that judgment was coming – and coming soon – for an unfaithful Church.

Then there is the example I have referred to elsewhere, where Darby remarks on the application of the Seven Churches in Revelation Chaps. 2 and 3, to the history of the Church as an interesting new insight though it had been in circulation for years.

Edward Synge might be an example. Darby worked with him at least as early as 1829. Edward Synge is described as having a: “new creed of biblical fundamentalism … equally distant from protestant and catholic. He expressed the opinion that being a member of any institutional church, whether protestant or catholic, was inconsequential in comparison to reading the bible”.

It has been impossible to discover more accurately what Synge’s views were (though a Synge descendant who is also working in this direction has been kind enough to remain in contact with me over the subject for some years now and we hope to progress).

The end result of Darby’s views on the Church and on prophecy may have carried his individual stamp, but they were definitely influenced and “supplied” by many others.

ibid.

During the early nineteenth century America experienced a social-economic boom. On the back of this prosperity came the “Roaring Twenties”, which brought with it such deprivation and immorality as America had not known. The American Church took a stand against what it considered to be a turning away from God unto ungodliness, and openly preached against it. In fact there was a conscience reinforcement by the majority of conservative churches against this social looseness, and a denouncing of it from many pulpits and street preachers. This resulted in many churches withdrawing more narrowly from society and the formulation of a new kind of Christianity known as Fundamentalism.

Due to the moral sate of American, many of its preachers thought that the world was coming to an end and that the Lord Jesus was about to return. This believe in itself was by no means unscriptural, but taught by the Apostles themselves. However, the dispensational teachings of John Nelson Darby was about to impact certain of these preachers with devastating effects upon the conservative churches of America.

Darby travelled to America on a number of occasions and taught his theories in several gatherings. One such being the church of Dr. Brookes, a Presbyterian minister. C. I. Scofield was, at that time, a student of Brookes’ Bible class and later took Darby’s teachings and published them in his own version of the Bible. Of this Bible, Albertus Pieters said, it is “one of the most dangerous books on the market.” To lean more about C. I. Scofield, his character and Reference Bible. please go >> here.

Darby taught that he had “Revived Precious Truth,” when in fact what he had done was revived the teaching of those who opposed truth.

“Darby’s dispensational views would however probably have remained the exotic preserve of the dwindling and divided Brethren sects were it not for the energetic efforts of C.I. Scofield and his associates to introduce them to a wider audience in America and the English speaking British Empire and bestow a measure of respectability through his Scofield Reference Bible. The publication of the Scofield Reference Bible in 1909 by the Oxford University Press was something of a innovative literary coup for the movement, since for the first time, overtly dispensationalist notes were added to the pages of the biblical text. What distinguishes Darby’s scheme and subsequent dispensationalists from the earlier attempts to categorise redemptive history is the conviction that the dispensations are irreversible and progressive. While such a dispensational chronology of events was largely unknown prior to the teaching of Darby and Scofield, the Scofield Reference Bible became the leading bible used by American Evangelicals and Fundamentalists for the next sixty years.”

Sizer. op. cit.

It was within the ranks of these Fundamentalist church groups where Dispensationalism flourished and soon became confused with conservative Christianity. It was also during this period of American history that quite a large number of independent, trans-denominational religious movements, such as Mormonism, Millerism (from which the Jehovah’s Witnesses emerged), and the Seventh-day Adventists, were conceived; each proclaiming to be the only form of true Christianity [see footnote]. It wasn’t long before the Dispensationalist Fundamentalist groups were claiming the same and begin to despise those who, unlike themselves, had not received this “new light.” As Philip Mauro explains.

I even enjoyed a complacent sense of superiority because thereof, and regarded with feelings of pity and contempt those who had not received the “new light” and were unacquainted with this up-to-date method of “rightly dividing the word of truth.”

Mauro. op. cit.

As with every new religious movement, the claim to supremacy is endemic. As we have already seen this was no different with Dispensationalism; John Nelson Darby considered those who did not agree with his novel theories to be apostate, separating from them and refusing to have any fellowship with them. Ironically it was those who rejected Darby’s teachings who had a Scriptural basis to refuse fellowship, not Darby. But the rejection of those who actually adhere to the truth is a mark of most sects and cults. C. I Scofield was to play a major part in the further separation of these American Fundamentalist groups.

Not a great deal has been written about Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, and it is not surprising when any research is made into his history and character. He is very well known as the author of the Scofield Reference Bible, but little else is known about him. It may surprise some to learn that Cyrus Scofield was a fraud and that his conversation to Christ is someone dubious. This is not based on any kind of prejudice against the man, but upon evidence that has resulted in researching Scofield’s background. The following is how one newspaper described him (although his name was misspelt) on appointment of his ministerial post in Texas.

CYRUS I. SCHOFIELD IN THE ROLE OF A CONGREGATIONAL MINISTER

“CYRUS I. SCHOFIELD, formerly of Kansas, late lawyer, politician and shyster generally has come to the surface again, and promises once more to gather around himself that halo of notoriety that has made him so prominent in the past. The last personal knowledge Kansans have had of this peer among scallywags was when about four years ago, after a series of forgeries and confidence games, he left the state and a destitute family and took refuge in Canada. For a time he kept undercover; nothing being heard of him until within the past two years when he turned up in St. Louis, where he had a wealthy widowed sister living who has generally come to the front and squared up Cyrus’s little follies and foibles by paying good round sums of money. Within the past year, however, Cyrus committed a series of St. Louis forgeries that could not be settled so easily, and the erratic young man was compelled to linger in the St. Louis jail for a period of six months.

“Among the many malicious acts that characterized his career was one peculiarly atrocious that has come under our personal notice. Shortly after he left Kansas, leaving his wife and two children dependent upon the bounty of his wife’s mother, he wrote his wife that he could invest some $1,300 of her mother’s money, all she had, in a manner that would return big interest. After some correspondence. he forwarded them a mortgage, signed and executed by one Charles Best, purporting to convey valuable property in St. Louis. Upon this, the money was sent to him. Afterwards the mortgages were found to be base forgeries, no such person as Charles Best being in existence, and the property conveyed in the mortgage fictitious.

“In the latter part of his confinement, Schofield, under the administration of certain influences, became converted, or professedly so. After this change of heart, his wealthy sister came forward and paid his way out by settling the forgeries, and the next we hear of him he is ordained as a minister of the Congregational Church, and under the chaperonage of Rev. Goodell, one of the most celebrated divines of St. Louis. He causes a decided sensation.

“It was known that Schofield was separated from his wife, but he had said that the incompatibility of his wife’s temper and her religious zeal in the Catholic Church was such that he could not possibly live with her.

“A representative of “The Patriot” met Mrs. Schofield today, and that little lady denies, as absurd, such stories. There were never any domestic clouds in their homes. They always lived harmoniously. As to her religion, she was no more zealous than any other church member. She attended service on the sabbath and tried to live as becomes a Christian woman and mother. It was the first time she had ever heard the objection raised by him. As to supporting herself and children, he had done nothing.

‘Once in a great while, say every few months, he sends the children about $5, never more. I am employed with A. L. Gignac and Co. and work for their support and mine. As soon as Mr. Schofield settles something on the children to aid me in supporting them and giving them an education, I will gladly give him the liberty he desires. I care not who he marries, or when, but I do want him to aid me in giving our little daughters the support and education they should have.’ “

Atchison Patriot. August 27, 1881.

Scofield’s conversion has been held in doubt by one of his biographers.

The 1912 edition of Who’s Who in America places Scofield’s conversion sometime in 1879, and Trumbull indicates as much in his biography. However, the only definite dates in 1879 tend to raise doubts about what happened and when.

When did the conversion occur? Scofield says he was converted at the age of thirty-six, and it has been assumed the event did take place sometime before D. L. Moody’s 1879-80 Evangelistic Campaign. This places the conversion sometime after his thirty-sixth birthday on August 19, 1879 and before the first meeting of Moody’s ministers in St. Louis on November 25, 1879. As late as November 6, though, Cyrus was still involved with a forgery charge, and that case’s records do not agree with the picture of a new convert trying to right matters of the past. Of course, God forgives the past and changes a man into a new creature if he is really born again (I Cor. 5:17), but one expects to see a change of behaviour. The details of Cyrus’s conversion are not supported by public records, so we do not know the whole truth about the conversion of a man who has profoundly influenced the church.

Weston. op. cit.

Not only does any evidence of Scofileds’ Christian conversion seem to be lacking, but there is no evidence that he had any real founding in the Scriptures.

Remarkably, with such limited theological background and training, as well as little real scholarship, Scofield was able to profoundly alter Christian theology. Indeed, the shape of fundamentalism, which has claimed to be Orthodox Christianity, has been determined by the influence of dubious characters like Scofield.

** Born to a vicar and trained for the church, Coleridge’s early career was preoccupied with his plans for a Utopian commune, Pantisocracy, which he and Robert Southey planned to form in America. This plan was never realized, but Southey and Coleridge collaborated on several poems; most particularly, Coleridge contributed the apocalyptic vision of Joan in Book II of Southey’s Joan of Arc. This and other early writings combined a fervour for the reformation of government through revolution with religious philosophy, especially that of Hartley and Priestley. This mix earned him the attention of the Reverend Edward Irving whom he met in 1822. The companionship between the two began to fade as Irving grew increasingly more millenarian and authoritarian; Coleridge was left doubting his earlier philosophy as Irving misused Coleridge’s ideas on spirituality, particularly as Irving attempted a literal reading of the book of Revelation (Fulford, 21). After his encounter with Irving, Coleridge began to view the apocalypse of St. John as an historical writing rather than divinely inspired, a view largely influenced by his readings into the Cabbala and the works of German biblical scholar J.G. Eichhorn (Fulford, 27). His apocalyptic poems, especially Religious Musings, An Ode to the Departed Year, and France, perhaps reflecting this consideration of the revelation as historical rather than prophetic, appear hopeless, apocalyptic without the promise of a millennium (Paley 24).

Many Millerites were affiliated with the 19th century Restorationism. Many leaders of Millerism had also been leaders in the New England Christian Connexion. The anti-organizational tendencies of Restorationism resulted in the hesitancy of Millerite groups to organize into a denomination, and when Christ did not return in 1844, contributed to the many sects. Most of the descendants of Adventism are generally regarded as Evangelical in nature.

Similarly, dispensational Premillennialism is a trans-denominational movement, that is sometimes mistakenly connected directly with the Millerites. Dispensationalism arose during the final third of the 19th century, and unlike the Millerites interprets prophecy in a primarily futurist fashion. This movement developed independently, borrowing heavily but indirectly from earlier Millerites, with radical re-interpretation, so that dispensationalists rarely if ever display unitarian tendencies. Sabbatarianism is excluded, along with British Israelism, and in general end times Dispensationalism is considered protestant and mainstream evangelical, being a very common belief among Christian fundamentalists. Some dispensationalist groups, upon venturing to calculate the date of Christ’s return or interpreting the signs of the times, take on many of the apocalyptic characteristics of Millerite pioneers, but strictly speaking none of them are part of the Millerite Adventist movement.

The followers of the self-proclaimed prophetess, Englishwoman Joanna Southcott, are frequently listed in the Millerite tradition, for lack of a similar place to put them, chiefly because of interesting parallels in the careers of Ms. Southcott and the Adventist Ellen G. White. Ms. Southcott is believed by her followers to be, in fact, the woman clothed with the sun, in the Book of Revelation. She prophesied that she herself was pregnant with the true Messiah, who was to be born on October 19, 1814 — these particular beliefs have no representation among Millerites. Ms Southcott died of dropsy in December of that year, but her followers continued to believe in the truth of her published prophecies and in the soon coming of Shiloh (a prophetic name for the Messiah). Her visions beginning in 1792 have strong affinity with Adventism, but are stylistically very unlike the writings of Mrs. White. The post-Disappointment Adventist Movement is frequently compared to the followers of Ms. Southcott, and there are some superficial resemblances of language and theme. The leaders of some branches of Southcottites are believed to have been post-Disappointment Millerites. Swedenborgianism and The United Order of Believers (Shakers), two other earlier millennial movements begun by ecstatic visionaries, have comparable similarities to the Millerites, and like the Mormons these groups had some influence on the religious climate of northwest New York state and territories to the west — but direct borrowing is not acknowledged, and after all, they are distinct movements. It is notable that a number of post-Disappointment Millerites joined the Shaker communities.

Charles Taze Russell’s Bible Student movement (from which the Jehovah’s Witnesses emerged in 1931 following a schism in 1917) had connections at the very beginning with the Millerite movement. Bahá’ís also credit Miller’s analysis of the time Christ’s return.

Copyright © 2007 A Gospel Preacher All Rights Reserved