I still regularly run across educated people who are unaware of or unconcerned about the very aggressive plan underway to bring all nations under (communist/totalitarian) global governance (The New World Order). With the internet, we have access to all the information we need to be informed about it, but unfortunately, alongside this easily accessed information, is a deliberately designed minefield of hype and fear that paints anyone looking into these things as ‘conspiratorial’ or, well, just not too bright.

The truth remains that the New World Order agenda is crucial to be informed about as it has it’s tentacles in virtually every aspect of society today; from economics, to social, political, education and religion.

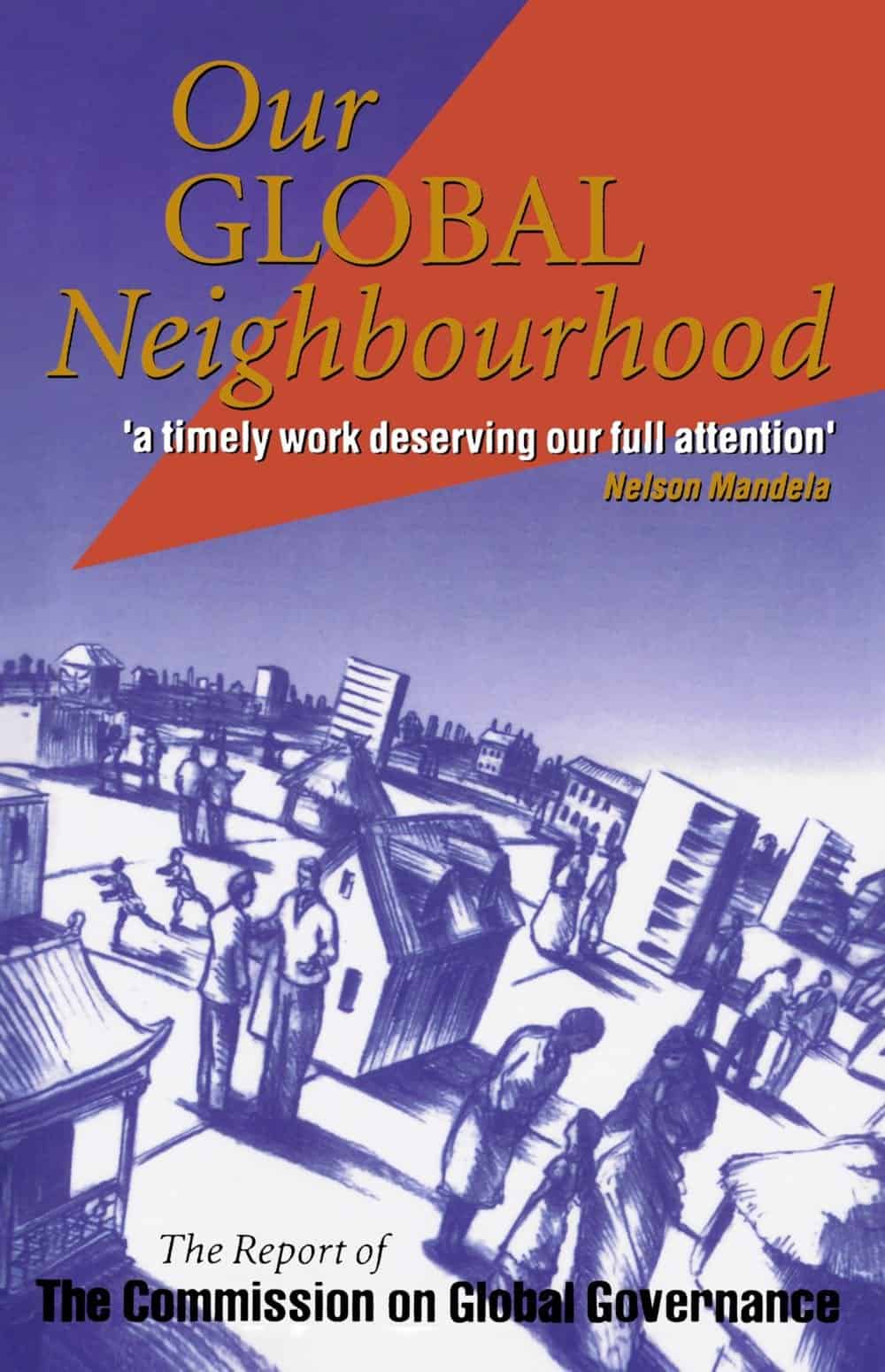

Here Henry Lamb of soverignty.net (currently found on bibliocassettes) presented a review of the book “Our Global Neighborhood”, released by the United Nations Commission on Global Governance. As with everything put out by the UN, the language in the book is subtle and misleading, reminiscent of communist propaganda everywhere. It’s amazing people still fall for it, since over and over again communism has been proven to fail. Also amazing is that this article was written 20 years ago and paints a picture of what we are seeing today.

Our Global Neighborhood – Report of the Commission on Global Governance – A Summary Analysis

by Henry Lamb – 1996

The Commission on Global Governance has released its recommendations in preparation for a World Conference on Global Governance, scheduled for 1998, at which official world governance treaties are expected to be adopted for implementation by the year 2000.

Among those recommendations are specific proposals to expand the authority of the United Nations to provide:

- Global taxation

- A standing UN army

- An Economic Security Council

- UN authority over the global commons

- An end to the veto power of permanent members of the Security Council

- A new parliamentary body of “civil society” representatives (NGOs)

- A new “Petitions Council”

- A new Court of Criminal Justice (Accomplished in July, 1998 in Rome)

- Binding verdicts of the International Court of Justice

- Expanded authority for the Secretary General

These proposals reflect the work of dozens of different agencies and commissions over several years, but are now being advanced by the Commission on Global Governance in its report entitled Our Global Neighborhood (Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-19-827998-3, 410pp).

The Commission consists of 28 individuals, carefully selected because of their prominence, influence, and their ability to effect the implementation of the recommendations. The Commission is not an official body of the United Nations.

It was, however, endorsed by the UN Secretary General and funded through two trust funds of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), nine national governments, and several foundations, including the MacArthur Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation.

The Commission believes that world events, since the creation of the United Nations in 1945, combined with advances in technology, the information revolution, and the now-global awareness of impending environmental catastrophe, create a climate in which the people of the world will recognize the need for, and the benefits of, global governance.

Global governance, according to the report,

“does not imply world government or world federalism.”

Although the difference between “world government” and “global governance” has been compared to the difference between “rape” and “date-rape,” the system of governance described in the report is a new system.

There is no historic model for the system here proposed, nor is there any method by which the governed may decide whether or not they wish to be governed by such a system. Global governance is a procedure toward defined objectives that employs a variety of methods, none of which give the governed an opportunity to vote “yes” or “no” for the outcome.

Decisions taken by administrative bodies, or by bodies of appointed delegates, or by “accredited” civil society organizations, are already implementing many of the recommendations just published by the Commission.

The Foundation for Global Governance

The foundation for global governance is the belief that the world is now ready to accept a “global civic ethic” based on “a set of core values that can unite people of all cultural, political, religious, or philosophical backgrounds.” This belief is reinforced by another belief:

“that governance should be underpinned by democracy at all levels and ultimately by the rule of enforceable law.”

The report says:

“We believe that all humanity could uphold the core values of respect for life, liberty, justice and equity, mutual respect, caring, and integrity.”

In the fine print, these lofty values lose much of their appeal. Respect for life, for example, is not limited to human life. “Respect for life” actually means equal respect for all life.

The Global Biodiversity Assessment (Section 9), prepared under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme, describes in great detail the biocentric view that “humans are one strand in nature’s web,” consistent with the biocentric view that all life has equal intrinsic value.

Some segments of humanity may balk at extending to trees, bugs, and grizzly bears the same respect for life that is extended to human beings.

“Next to life, liberty is what people value most,” the report says. It also says: “The impulse to possess turf is a powerful one for all species; yet it is one that people must overcome.”

It also says:

“global rules of custom constrain the freedom of sovereign states,” and “sensitivity over the relationship between international responsibility and national sovereignty [is a] considerable obstacle to the leadership at the international level,” and “Although states are sovereign, they are not free individually to do whatever they want.”

Maurice Strong, a member of the Commission, and a likely candidate for the position of Secretary General, said in an essay entitled Stockholm to Rio: A Journey Down a Generation:

“It is simply not feasible for sovereignty to be exercised unilaterally by individual nation-states, however powerful. It is a principle which will yield only slowly and reluctantly to the imperatives of global environmental cooperation.”

The core value of “justice and equity” is the basis for sweeping changes in the UN as proposed by the Commission.

The Commission has determined that:

“Although people are born into widely unequal economic and social circumstances, great disparities in their conditions or life chances are an affront to the human sense of justice. A broader commitment to equity and justice is basic to more purposeful action to reduce disparities and bring about a more balanced distribution of opportunities around the world.

A commitment to equity everywhere is the only secure foundation for a more humane world order…. Equity needs to be respected as well in relationships between the present and future generations. The principle of intergenerational equity underlies the strategy of sustainable development.”

“Mutual respect” is broadly defined as “tolerance.”

“Some assertions of particular identities may in part be a reaction against globalization and homogenization, as well as modernization and secularization. Whatever the causes, their common stamp is intolerance.”

Individual achievement and personal responsibility are counter to the value of “mutual respect” as suggested in the UN’s World Core Curriculum, authored by Robert Muller, Chancellor of the UN University and former Deputy Secretary General to three UN Secretaries General.

The Robert Muller School World Core Curriculum Manual (November, 1986) says:

“The idea for the school grew out of a desire to provide experiences which would enable the students to become true planetary citizens through a global approach to education.”

The first principle of the curriculum is to:

“Promote growth of the group idea, so that group good, group understanding, group interrelations and group goodwill replace all limited, self-centered objectives leading to group consciousness.”

The value of “caring” is institutionalized in the Commission’s proposals:

“The task for governance is to encourage a sense of caring, through policies and mechanisms that facilitate co-operation to help those less privileged or needing comfort and support in the world.”

“Integrity” is defined to be the adoption and practice of these core values and the absence of corruption. As the world adopts these core values, the Commission believes a “global ethic” will emerge.

Global governance will,

“Embody this ethic in the evolving system of international norms, adapting, where necessary, existing norms of sovereignty and self-determination to changing realities.”

The effectiveness of this global ethic,

“will depend upon the ability of people and governments to transcend narrow self-interests and agree that the interests of humanity as a whole will be best served by acceptance of a set of common rights and responsibilities. Without the objectives and limits that a global ethic would provide, however, global civil society could become unfocused and even unruly. That could make effective global governance difficult.”

Among the “rights” such a global ethic would bestow upon all people are:

- A secure life

- An opportunity to earn a fair living

- Equal access to the global commons

The right to “a secure life” means much more than freedom from the threat of war.

“Human security includes safety from chronic threats such as hunger, disease, and repression, as well as protection from sudden and harmful disruptions in the patterns of daily life. The Commission believes that the security of people must be regarded as a goal as important as the security of states.”

Herein lies a significant expansion of the responsibilities of the United Nations.

Until now, the UN’s responsibility was limited to its member states. The Commission’s proposals will give to the UN responsibility for the security of individuals within the boundaries of member states. This shift is extremely significant as we shall see when we examine proposed changes in the structure and authority of UN organizations.

The right to a secure life also means the right to live on a secure planet.

“Human activity…combined with unprecedented increases in human numbers…are impinging on the planet’s basic life support systems. Action must be taken now to control the human activities that produce these risks…. In confronting these risks, the only acceptable path is to apply the `precautionary principle’.”

Clearly, the Commission sees the UN as the global authority for protecting the environment.

The right to earn a “fair living” carries with it far-reaching implications. The Commission discusses at length what is “fair” and what is not. It is not fair, for example, for the developed countries, which contain 20 percent of the population, to use 80 percent of the natural resources.

It is not fair for the permanent members of the Security Council to have the right of veto.

In general, it is not fair for one segment of the population to be rich while another segment of the population is poor.

“Unfair in themselves, poverty and extreme disparities of income fuel both guilt and envy when made more visible by global television. They demand, and in recent decades have begun to receive, a new standard of global governance.”

The right to earn a fair living implies that there must be some kind of a job available from which people may earn their living.

Under the auspices of a new Economic Security Council, which we will discuss later, the Commission would give the UN responsibility for seeing that all people would have “an opportunity to earn a fair living.”

The Commission sees pollution of the global atmosphere and the depletion of ocean fisheries as inadequacies of global governance.

“We propose, therefore, that the Trusteeship Council… be given the mandate of exercising trusteeship over the global commons. Its functions would include the administration of environmental treaties…. It would refer any economic or security issues arising from these matters to the Economic Security Council or the Security Council.”

Trusteeship over the global commons provides the basis to levy user fees, taxes and royalties for permits to use the global commons.

Global commons are defined to be:

“the atmosphere, outer space, the oceans, and the related environment and life-support systems that contribute to the support of human life.”

This broad definition of the global commons would give the UN authority to deal with environmental matters inside the borders of sovereign states, and on privately owned property.

The foundation of global governance is a set of core values, a belief system, which contains ideas that are foreign to the American experience, and ignores other values and ideas that are precious to the American experience. The values and ideas articulated in the Commission’s report are not new. They have been tried, under different names, in other societies. Often, the consequences have been devastating.

These values, under new names, have been emerging in UN documents since the late 1980s, and have dominated international conferences, agreements, and treaties since 1992. This set of core values underlies Agenda 21 adopted in Rio de Janeiro.

Virtually every international treaty and agreement introduced during this decade reflects this set of core values.

The Commission’s recommendations to achieve global governance seek to enforce these values through the programs authorized and implemented by a global bureaucracy growing from a revitalized and restructured United Nations system.

The Structure of Global Governance

The UN Security Council is the supreme organ of the United Nations system. Originally, the Council had eleven members, of which China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States were permanent members with veto power. The other six positions rotated in two- year terms among the remaining members of the UN General Assembly.

The Council now has 15 members which would be increased to 23. The proposal stops short of recommending the elimination of permanent status, but does recommend that the remaining members serve as “standing members” until a full review of member status can be conducted, including the permanent members, “in the first decade of the next century.” A phase-out of the veto power of permanent members is recommended.

Perhaps more important are the proposed new principles under which the Security Council may take action.

“We propose that the following be used as norms for security policies in the new era:

- All people, no less than all states, have a right to a secure existence

- Global security policy should be to prevent conflict and war and to maintain the integrity of the planet’s life-support systems by eliminating the economic, social, environmental, political and military conditions that generate threats to the security of people and the planet

- Military force is not a legitimate political instrument except in self-defense or under UN auspices

- The production and trade in arms should be controlled by the international community”

The Commission believes and recommends,

“that it is necessary to assert… the rights and interests of the international community in situations within individual states in which the security of people is violated extensively.

We believe a global consensus exists today for a UN response on humanitarian grounds in cases of gross abuse of the security of people.”

Subtle, carefully crafted language significantly expands the mission and authority of the UN Security Council to intervene in the affairs of sovereign states when it determines that the security of individuals is in jeopardy.

Security of individuals, under the set of core values and the new global ethic, includes an opportunity to earn a fair living, and equal access to the global commons. This expanded authority includes military intervention – as a last resort.

The Security Council would also be empowered to raise a standing army. Article 43 of the UN Charter authorizes such a force, but has never been activated.

The Commission says:

“It is high time that this idea – a United Nations Volunteer Force – was made a reality.”

Such a force would be under the exclusive authority of the UN Security Council and under the day-to-day command of the UN Secretary General. It would maintain its own support and mobilization capabilities and be available for “rapid deployment” anywhere in the world.

The Commission envisions a small, highly trained, well equipped force of 10,000 troops for immediate intervention while more conventional “peace keeping” forces are assembled from member nations.

A Restructured Trusteeship Council

The Trusteeship Council is an original principal organ of the United Nations system.

Created to oversee nations in transition from colonies to independence, its work was concluded in 1994 when the last of the colonies, Palau in the South Pacific, gained its independence.

The Commission has proposed amending Chapters 12 and 13 of the UN Charter to give the Trusteeship Council authority over the global commons, and to reconstitute the Council with a fixed number of members including qualified members from “civil society.” This proposal is another extremely significant step in the creation of a new form of governance.

A “qualified member from civil society” means a representative from an accredited NGO (non-government organization).

The status of NGOs is elevated even further in the Commission’s recommendations which we will be see later.

Here, however, for the first time, unelected, self-appointed, environmental activists are given a position of governmental authority on the governing board of the agency which controls the use of atmosphere, outer space, the oceans, and, for all practical purposes, biodiversity. This invitation for “civil society” to participate in global governance is described as expanding democracy.

The work assigned to the Trusteeship Council is now the responsibility of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), which was an original principal organ of the UN system. The Commission proposes that ECOSOC be retired and all the agencies and programs under its purview be shifted to the Trusteeship Council.

The United Nations Environment Programme, along with all the environmental treaties under its jurisdiction, would ultimately be governed by a special body of environmental activists, chosen only from accredited NGOs appointed by delegates to the General Assembly who are themselves appointed by the President.

The Commission says:

“The most important step to be taken is the conceptual one that the time has come to acknowledge that the security of the planet is a universal need to which the UN system must cater.”

The environmental work program of the entire UN system will be authorized and coordinated by this body.

Enforcement will come from an upgraded Security Council, and from the new Economic Security Council.

The New Economic Security Council

Described as an “Apex Body,” the Economic Security Council (ESC) is proposed to have,

“the standing in relation to international economic matters that the Security Council has in peace and security matters.”

The new ESC would be a deliberative, policy body rather than an executive agency. It would work by consensus without veto power by any member.

“The time is now ripe – indeed, overdue – to create a global forum that can provide leadership in economic, social and environmental fields.”

According to the Commission, the new ESC would:

- Continuously assess the overall state of the world economy

- Provide a long-term strategic policy framework to promote sustainable development

- Cure consistency between the policy goals of the international economic institutions (World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization,Global Environment Facility, and others)

- Study proposals for financing public goods by international revenue raising.

(Public goods are defined to be: “The rules and sense of order that must underpin any stable and prosperous system…. It is in their nature not to be provided by markets or by individual governments acting in isolation”)

The agenda to be addressed by the ESC includes:

“long-term threats to security in its widest sense, such as shared ecological crises, economic instability, rising unemployment…mass poverty…and with the promotion of sustainable development.”

The Commission recommends that the ESC have no more than 23 members, that it be headed by a new Deputy Secretary-General for Economic Co-operation and Development, and that the gross domestic product (GDP) of all member nations be measured by and based upon “Purchase Power Parity (PPP).”

PPP is an accounting device, which (according to a chart on page 163 of the report) transforms the 1991 U.S. trade deficit of $28 billion into a trade surplus of $164 billion.

Both the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) would be brought under the authority of the new ESC.

The Commission believes:

“for economic growth to raise the living standards of the poor and be environmentally sustainable, trade has to be open and based on stable, multilaterally agreed rules.”

The ESC would be given authority over telecommunications and multimedia.

Since the atmosphere and outer space are “global commons” assigned to the Trusteeship Council, businesses that use the air waves and satellites would be subject to the policies of the ESC.

The Commission says:

“Civil society itself should try to provide a measure of global public service broadcasting not linked to commercial interests. The highest priority should be given to examining how an appropriate system of global governance can be created for overseeing the `global information society’ through a common regulatory approach.”

The Commission calls on the WTO to give poor countries preferential treatment in license allocations and to create rules to counter the influence of “national monopolies.”

Without this high-level ESC, the Commission fears that,

“the global neighborhood could become a battleground of contending economic forces, and the capacity of humanity to develop a common approach will be jeopardized.”

The ESC is expected to address the problem of tariffs and quotas, and,

“A wide range of what used to be considered purely as national concerns: nationally created technical and product standards, different approaches to social provision and labour markets, competition policy, environmental control, investment incentives, corporate taxation, and different traditions of commercial and intellectual property law, of corporate governance, of government intervention, and of cultural behavior.”

The ESC is designed to centralize and consolidate policy making for not only world trade, but also for the international monetary system and world development.

The Commission says:

“there is a broad consensus on many of the elements: an understanding of the importance of environmental sustainability; financial stability; and a strong social dimension to policy, emphasizing education (especially of women), health, and family planning.”

To deal with third-world debt, the Commission recommends that a system be established,

“akin to corporate bankruptcy, whereby a state accepts that its affairs will, for a while, be placed under the management of representatives of the international community and a fresh start is made, wiping much of the slate clean.”

The ESC is expected to facilitate “technology transfer” which is “crucial to development” in developing countries.

The ESC is expected to establish immigration policies because,

“there is an underlying inconsistency – even hypocrisy – in the way many governments treat migration. They claim a belief in free markets (including labour markets), but use draconian and highly bureaucratic regulations to control cross-border labour migration.”

Environmental policies are to be under the authority of the Trusteeship Council, but implementation and enforcement of those policies will largely be a function of the ESC. Implementation measures will be coordinated through UN organizations and NGOs.

The Commission recognizes that:

“Non-governmental organizations, such as the World Conservation Union (International Union for the Conservation of Nature – IUCN), the World Resources Institute (WRI), and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), have also made important contributions by creating a climate conducive to official action to improve environmental governance.”

(Co-chair of the Commission on Global Governance is the immediate past president of the IUCN, Shirdath Ramphal; the IUCN created the WWF in 1961, and the WWF created the World Resources Institute in 1982.

The immediate past president of WRI, Gustave Speth, is now head of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and WRI’s chief policy analyst, Rafe Pomerance, is now Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Environment, Health and Natural Resources).

The Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD), created as a result of the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), (headed by Maurice Strong) is expected to be,

“the focal point within the UN system for coherence and co-ordination of programs undertaken by various UN agencies. The CSD should not, however, be seen simply as an administrative coordinating body.

It exists to give political leadership more generally in the field of sustainable development, in particular in implementing Agenda 21 as agreed at Rio.”

The Commission recognizes that:

“sustainable development cannot be achieved solely through government action or market forces. The growing reliance on non-governmental organizations and institutions as partners with government and business in achieving economic progress is leading to more participatory development. Involving agents of civil society leads to programs and projects that are more focused on people and more productive.”

To insure greater involvement by “civil society,” the Commission has formalized proposals to elevate the status of NGOs.

The Machinery of Global Governance

The Commission recommends the creation of two new bodies:

(1) an Assembly of the People

(2) a Forum of Civil Society

“What is generally proposed is the initial setting up of an assembly of parliamentarians, consisting of representatives elected by existing national legislatures from among their members, and the subsequent establishment of a world assembly through direct election by the people.”

The Forum of Civil Society would consist of “300 – 600 representatives of organizations accredited to the General Assembly….”

The Forum would meet annually prior to the meeting of the UN General Assembly.

“The considered views of the Forum would be a qualitative change in the underpinnings of global governance.”

NGO participation in global governance is an essential feature, and is, in fact, the dimension of governance that is totally new.

It is no longer just an idea. It is a demonstrated fact of life which the Commission now seeks to institutionalize through legal status. It is the machinery of global governance which is organized and coordinated from the highest chambers of governance at the United Nations, to the most local bodies of governance, including County Commissions, City Councils, and even to local watershed councils.

The idea of NGO participation in global governance is as old as the United Nations. Julius Huxley, who founded the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), in 1946, also founded the IUCN in 1948.

It was the IUCN that effectively lobbyied the UN General Assembly in 1968 to adopt Resolution #1296, which establishes a policy for “accrediting” certain NGOs.

The IUCN is accredited to at least six different UN organizations.

Moreover, it is the premier international NGO claiming a membership of 53 international NGOs, 550 national NGOs, 100 government agencies, and 68 sovereign nations. The current president of the IUCN is Jay Hair, former president of America’s largest NGO, the National Wildlife Federation.

The IUCN created the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) which in turn, created the World Resources Institute (WRI). These three NGOs share publication credit with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) on virtually every major document on the environment that has been released since 1972.

As of 1994, there were 980 accredited NGOs. These NGOs are accredited because of their demonstrated support of issues being advanced by the United Nations. A single NGO is selected to coordinate activities within each issue area. In addition to the Internet, NGO coordination information is published by the WRI in a publication called Networking.

Activity of non-accredited NGOs is coordinated through membership in the IUCN.

The IUCN Annual Report for 1993 claims more than 6000 “experts” in their network who serve as volunteers “on Technical Advisory Committees, Regional Advisory Councils, Working Groups and Task Forces. Taken together, these voluntary groups are an immense strength of the Union.”

According to the Commission’s report, 28,900 international NGOs are known to exist, and many are directly involved in advancing the agenda of global governance.

At UNCED, for example, 7,892 NGOs were certified to participate in the “civil society forum” which preceded the actual conference. Many of the NGOs participated in the preliminary Preparatory Committee Meetings, or “PrepComs,” and were prepared and present to lobby the official delegates to the conference. This procedure is followed at virtually every global and regional conference.

This procedure is now being applied to domestic policy. Members of the international NGO community have strong national constituencies, and enormous staff and money capabilities. Global issues, such as the Biodiversity Treaty, which require national or local action, become the focus of the domestic agenda for national NGOs.

The structure and mechanics of “civil society” participation in global governance is further revealed in a variety of documents originating from the UN organizations and from the IUCN, WWF, and the WRI.

Most often, the term “Public/Private Partnerships” is used to describe and define “civil society” participation.

At the lowest, “on-the-ground” level, NGOs are present and prepared to lobby on issues relating to a particular watershed, or a particular project under consideration by a local zoning board. Public/Private Partnerships encourage the creation of “boards” or “councils” which are supposed to represent the interests of all the “stakeholders.”

In reality, these boards are encouraged because well-prepared NGOs are most often able to dominate the outcome.

At the local level, NGOs are frequently full-time professionals, paid by a not-for-profit organization, funded through the coordinated efforts of the Environmental Grantmakers Association or the federal government. The other “stakeholders” in these partnerships are business people who work for a living and simply want to take care of the environment, but have too little time to become experts on the issues.

Within the broader agenda, NGOs within these local partnerships coordinate with NGOs assigned to multi-county, or regional councils.

The NGOs that are assigned to regional councils and partnerships coordinate with the NGOs that set the national agenda. And they are, of course, the same NGOs that are accredited to the UN, or are members of the IUCN.

Deep within the 1,100 or more pages of the Global Biodiversity Assessment, there is a discussion of this procedure which, ideally, would culminate with a “Bioregional Council,” consisting of “stakeholders,” but dominated by affiliates of “accredited” NGOs, that would have ultimate authority over all local land and resource use decisions.

To further strengthen the participation of NGOs, the Commission recommends the creation of “a new ‘Right of Petition’ available to international civil society.”

The recommendation calls for the creation of a Council for Petitions, “a high-level panel of five to seven persons, independent of governments and selected in their personal capacity.

It would be appointed by the Secretary-General with approval of the General Assembly. It should be a Council that holds in trust ‘the security of people’ and makes recommendations to the Secretary-General, the Security Council, and the General Assembly.” This new mechanism provides a direct route from the local, “on-the-ground” NGO affiliates of national and international NGOs to the highest levels of global governance.

Although this mechanism has not yet been formally incorporated into the UN system, the procedure is being used.

For example, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, a group of affiliated NGOs, recently petitioned the World Heritage Committee of UNESCO asking for intervention in the plans of a private company to mine gold on private land near Yellowstone Park. The UNESCO Committee did intervene, and immediately listed Yellowstone as a “World Heritage Site in Danger.”

Under the terms of the World Heritage Convention, the United States is required to protect the park, even beyond the borders of the park, and onto private lands if necessary.

Enforcing Global Governance

“From the outset, the World Court was marginalized… states were free to take it or leave it, in whole or in part. The rule of law was asserted and, at the same time, undermined.”

The Commission intends to remedy this situation. Historically, scholars have argued that international law was not really law because there was no international legislature to create it, nor an international police force to enforce it.

The Commission’s recommendations remedy these problems.

The UN International Law Commission (ILC), a little-known subsidiary organ of the General Assembly created in 1947, is expected to expand its activity to include developing and drafting proposed international law. The IUCN now provides this service through its Environmental Law Centre.

The Commission recommends that treaties and agreements be written to include binding adjudication by the World Court, and that all nations “accept compulsory jurisdiction of the World Court.” The WTO is a step in this direction.

Members agree in advance to accept WTO decisions and not seek bilateral resolution of disputes.

“The very essence of global governance is the capacity of the international community to ensure compliance with the rules of society.”

The New International Criminal Court

The ILC has already developed the statutes necessary to create a new International Criminal Court.

The example used to justify this court is Lybia’s refusal to extradite the accused terrorists responsible for the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie.

“An International Criminal Court should have an independent prosecutor or a panel of prosecutors….Upon receipt of a complaint, the prosecutor’s primary responsibility would be to investigate an alleged crime.

The prosecutor would, of course, have to act independently and not seek or receive instructions from any government or other source.”

The Commission recognizes that these recommendations may encounter opposition, and warns that,

“internal political processes within nation-states… may become obstacles to adoption of international standards. In the contemporary world, populist action has the potential to strike down the carefully crafted products of international deliberation…

Yielding to internal political pressure can in a moment destroy the results of a decade of toil.”

Although not explicitly referenced, this revealing commentary likely points to the outpouring of grassroots opposition to the Biodiversity Treaty when presented to the Senate for ratification in the 103rd Congress.

The treaty – signed by President Clinton, approved by the Democratically-controlled Foreign Relations Committee, championed by virtually all the accredited NGOs, and expected to be approved by a wide margin, – never reached the floor for a vote because of “populist action.”

The Commission does not discuss why the activity of accredited NGOs and their affiliates is “expanding democracy” through civil society participation, while at the same time, activity of non-accredited civil society is “political pressure,” and “populist action.”

Financing Global Governance

The Commission says:

“Past reports recommending globally redistributive tax principles have received short shrift. The time could be right, however, for a fresh look and a breakthrough in this area.

The idea of safeguarding and managing the global commons – particularly those related to the physical environment – is now widely accepted; this cannot happen with a drip-feed approach to financing.

And the notion of expanding the role of the United Nations is now accepted in relation to military security.”

Currently, total UN expenditures are slightly more than $11 billion annually, although not all the costs of peacekeeping activities are reflected through the UN system.

The cost of implementing Agenda 21 was estimated in 1992 to be $600 billion per year. The proposed expansion of the UN system, and the proposals to expand programmatic responsibility suggest staggering costs.

Currently, UN costs are paid by member nations in the form of assessments and voluntary contributions.

The UN Charter says the costs will be paid by member nations as apportioned by the General Assembly, with no nation paying more than 25 percent. The United States is assessed 25 percent, contributes substantially to the volunteer programs, and ultimately pays more than 30 percent of the peacekeeping costs.

Because the UN has no power to enforce payment of either assessments or voluntary contributions, the Commission says,

“the industrialized countries… have severely constrained the exercise of the Assembly’s collective authority. A start should be made in establishing practical, if initially small-scale, schemes of global financing to support specific UN operations.”

The United States has often withheld payment as a means of influencing UN policy. The Commission is careful to avoid giving the UN direct taxing power.

“We specifically do not propose a taxing power located anywhere in the UN system. User charges, levies, taxes – global revenue-receiving arrangements of whatever kind – have to be agreed globally and implemented by a treaty or convention.”

Such an arrangement appears in the Law of the Seas treaty which authorizes a UN organization to charge application fees and royalties to companies wishing to mine the sea bed – even though the United States has not ratified the treaty.

The Commission’s refusal to recommend taxing power for the UN while advancing dozens of global revenue-raising schemes is similar to declaring that “global governance” is not “world government.”

The Commission says,

“It would be appropriate to charge for the use of some common global resources. Another idea would be for corporate taxation of multinational companies.”

The favored scheme was first advanced by Nobel Prize winner, James Tobin. He has proposed a tax on international monetary exchange which would yield an estimated $1.5 trillion per year.

“Charges for use of the global commons have a broad appeal on grounds of conservation and economic efficiency as well as for political and revenue reasons.”

The Commission supports a $2 per barrel tax on oil, which automatically escalates to $10 per barrel in 10 years.

“A carbon tax introduced across a large number of countries or a system of traded permits for carbon emissions would yield very large revenues indeed.”

Other recommendations for global revenues include:

- A surcharge on airline tickets for use of the global commons

- A charge on ocean maritime transport

- User fees for ocean fishing

- Special user fees for activities in Antarctica

- Parking fees for geostationary satellites

- Charges for user rights of the electromagnetic spectrum

“We urge the evolution of a consensus to help realize the long discussed and increasingly relevant concept of global taxation.”

Conclusion

Many of the recommendations contained in this report have already been incorporated into treaties, agreements, and proposals initiated by the international community.

Some have already been implemented. The Commission has called for the General Assembly to schedule a World Conference on Governance in 1998.

Preparatory work has already begun. PrepComs will be conducted to develop documents on global governance – similar to the procedure used to develop the documents presented at Rio – which are to be adopted at the 1998 Conference and ratified for implementation by the year 2000. Only “accredited” NGOs will be allowed to participate in the PrepComs.

Only accredited NGOs and their affiliates will participate in the adoption strategy.

More importantly, only delegates appointed by the President of the United States will be able to cast a vote on all the issues that so dramatically affect every American. The current Presidential appointees are the very people who helped develop the proposals from their various positions with accredited NGOs.

The NGO machinery of global governance is at work in America. Their activity includes agitation at the local level, lobbying at the national level, promoting the celebration of the UN’s 50th anniversary, producing studies to justify global taxation, and paying for television ads that elevate the image of the UN.

The strategy to advance the global governance agenda specifically includes programs to discredit individuals and organizations that generate “internal political pressure” or “populist action” that fails to support the new global ethic. The national media has systematically portrayed dissenting voices as right-wing-extremist, militia-supporting fanatics.

Consequently, the vast majority of American citizens have no idea how far the global governance agenda has progressed.

This year, 1996, may be the last opportunity the world has to avoid, or at least to influence the shape of global governance. The United States is the only remaining power strong enough to influence the United Nations.

Those voices now speaking for all Americans in the United Nations are cheering the forces that would diminish national sovereignty and render individual liberty and property rights relics of the past. If the current voices representing the United States continue to push for global governance, the world will be committed to a course which will truly transform society more dramatically than the Bolshevik revolution transformed Russia.

The recommendations of the Commission, if implemented, will bring all the people of the world into a global neighborhood managed by a world-wide bureaucracy, under the direct authority of a minute handful of appointed individuals, and policed by thousands of individuals, paid by accredited NGOs, certified to support a belief system, which to many people – is unbelievable and unacceptable.

(Our Global Neighborhood: The Report of the Commission on Global Governance may be obtained from Oxford University Press. Call (919) 677-0977 ; paperback, $14.95, ISBN 0-19-827997-3, 410 pages.)

About the Commission on Global Governance

Former West German Chancellor, Willy Brandt, called a group of prestigious, international leaders to Konigswinter, Germany in January 1990.

They asked Ingvar Carlsson (then Prime Minister of Sweden), and Shirdath Ramphal (Secretary General of the Commonwealth and President of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and Jan Pronk (Minister for Development Co-operation of the Netherlands) to prepare a report on the opportunities for global governance.

The report was presented in April, 1991, in Stockholm, and Carlsson and Ramphal were asked to co-chair the new commission the report recommended. The Co-chairmen met with Boutros Boutros-Ghali, UN Secretary General, in April, 1992, to secure his endorsement of the effort.

By September, the Commission was established with 28 members and funding from two trust funds administered by the United Nations Development Program, nine national governments, and private foundations.

Meet the Commissioners

Ingvar Carlsson, Sweden Prime Minister of Sweden 1986-91, and Leader of the Social Democratic Party in Sweden.

Shirdath Ramphal, Guyana Secretary-General of the Commonwealth from 1975 to 1990, President of the IUCN, Chairman of the Steering Committee of the Leadership in Environment and Development Program; Chairman, Advisory Committee, Future Generations Alliance Foundation, Chancellor, University of the West Indies, and the University of Warwick in Britain, member of five international commissions in the 1980s, and author of Our Country, The Planet, written especially for the Earth Summit.

Ali Alatas, Indonesia Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia since 1988; permanent representative to the United Nations.

Abdlatif Al-Hamad, Kuwait Director-General and Chairman of the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development in Kuwait. Former Minister of Finance and Minister of Planning; member of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues; Board member of the Stockholm Environment Institute.

Oscar Arias, Costa Rica President of Costa Rica from 1986 to 1990; drafted the Arias Peace Plan which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize; founded the Arias Foundation for Peace and Human Progress.

Anna Balletbo i Puig, Spain Member of the Spanish Parliament since 1979; member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs and on Radio and Television; Executive Committee of the Socialist Party in Catalonia; General Secretary of the Olof Palme International Foundation; President of Spain’s United Nations Association; and activist on women’s issues since 1975.

Kurt Biedenkopf, Germany Minister-President of Saxony since 1990; member of the Federal Parliament; Secretary General of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany.

Allan Boesak, South Africa Minister for Economic Affairs for the Western Cape Region; Director of the Foundation for Peace and Justice; Chairman of the African National Congress (ANC); President of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches and a Patron of the United Democratic Front.

Manuel Camacho Solis, Mexico Former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Mayor of Mexico City; Mexico’s Secretary of Urban Development and Ecology.

Bernard Chidzero, Zimbabwe Minister of Finance; Deputy Secretary-General of UNCTAD; Chairman of the Development Committee of the World Bank and the IMF; and member of the World Commission on Environment and Development.

Barber Conable, United States President of the World Bank from 1986 to 1991; Chairman of the Committee on US-China Relations; Senior Advisor to the Global Environment Facility; member of the House of Representatives from 1965 to 1985; member of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution; and Trustee and member of the Executive Committee of Cornell University.

Jacques Delors, France President of the European Commision since 1985; Minister for Economics, Finance and Budget; Mayor of Clichy; and member of the European Parliament.

Jiri Dienstbier, Czech Republic Chairman of the Free Democrats Party; Chairman of the Czech Council on Foreign Relations; and Deputy Prime Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Enrique Iglesias, Uruguay President of the Inter-American Development Bank since 1988; Minister of External Relations; Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America; President, Central Bank of Uruguay; and Chairman of the Conference that launched the Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations resulting in the World Trade Organization.

Frank Judd, United Kingdom Member of the House of Lords; Member of Parliament; Under-Secretary of State for Defence; Minister for Overseas Development; Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth; and Director of Oxfam from 1985 to 1991.

Hongkoo Lee, Republic of Korea Deputy Prime Minister; Minister of National Unification; Ambassador to the United Kingdom; Professor of Political Science at Seoul National University; Director of the Institute of Social Sciences; and Chairman of Seoul’s 21st Century Committee.

Wangari Maathai, Kenya Founder and co-ordinator of the Green Belt Movement in Kenya; Chair of the National Council of Women of Kenya and spokesperson for non-government organizations at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio.

Sadako Ogata, Japan United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees since 1991; Director of the International Relations Institute; Representative to the UN; member of the Independent Commission on International Humanitarian Issues; and Chairman of the Executive Board of UNICEF.

Olara Otunnu, Uganda President of the International Peace Academy in New York; Foreign Minister from 1985 to 1986; Permanent Representative to the UN; and Chaired UN Commission on Human Rights.

I.G. Patel, India Chairman of the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme; Governor of the Reserve Bank of India; Chief Economic Adviser to the Indian Government; Permanent Secretary of the Indian Finance Ministry; Director of the London School of Economics and Political Science; Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund; and Deputy Administrator of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Celina Vargas do Amaral Peixoto, Brazil Director Getulio Vargas Foundation; Director-General of the Brazilian National Archives; Director of the Center of Research and Documentation on Brazilian History.

Jan Pronk, Netherlands Minister for Development Co-operation; Vice Chairman of the Labor Party; Member of Parliament; Deputy Secretary-General of UNCTAD; and Member of the Independent Commission on International Development issues.

Qian Jiadong, China Deputy Director-General of the China Centre for International Studies; Ambassador and Permanent Representative in Geneva to the United Nations; Ambassador for Disarmament Affairs; and member of the South Commission.

Marie-Angelique Savane, Senegal Director of the Africa Division of the UN Population Fund; Director of the UNFPA in Dakar; Advisor to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees; team leader at the UN Research Institute for Social Development; President of the Association of African Women for Research and Development; and member of the UNESCO Commission on Education for the 21st Century.

Adele Simmons, United States President of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; member of the Council on Foreign Relations; member of the UN High Level Advisory Board on Sustainable Development; member of President Carter’s Commission on World Hunger; and member of President Bush’s Commission on Environmental Quality.

Maurice Strong, Canada Chairman and CEO of Ontario Hydro; Chairman of the Earth Council; Secretary-General of Earth Summits I and II; and member of the World Commission on Environment and Development. (See ecologic, November/December, 1995)

Brian Urquhart, United Kingdom Scholar-in-Residence at the Ford Foundation’s International Affairs Program; United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs 1972 to 1986; Member of the Independent Commission on Disarmament and Security Issues.

Yuli Vorontsov, Russia Ambassador to the United States; Ambassador to the United Nations; Advisor to President Boris Yeltsin on Foreign Affairs; and served as Ambassador to Afghanistan, France, and India.