Between the congressional hearing for David Friedman, the visit of Benjamin Netanyahu, and President Trump’s refusal to address the rising tide of anti-Semitism, it’s been a tense time within the American Jewish community. For those on the right, Trump’s abandonment of the two-state solution, much like Friedman’s nomination, comes as an assurance that the new administration will firmly commit itself to an expansionist form of Zionism. And along with the presence of Jared Kushner within the President’s inner circle, keeping Friedman and Bibi in the wings is taken by many as a signal that Trump is not really an anti-Semite, despite surrounding himself with figures of questionable persuasion. According to this logic, the strong commitment by Trump and Steve Bannon to Israel undermines any suggestion that they harbor antipathy toward Jews. Yet, for many centrists and liberals, the idea of Jared Kushner and Steve Bannon working together causes endless confusion: How could the descendant of Holocaust survivors find common cause with the ideological leader of the alt-right?

The answer may lie in the history of the Zionist movement, a history which demonstrates that there is no inherent contradiction between Zionism and anti-Semitism. The two ideologies have in fact often worked in concert to achieve their shared goal: concentrating Jews in one place (so as to better avoid them in others). Even before the modern Zionist movement arose in the late 19th century, Christian philosophers and statesmen debated what to do with the “oriental” mass of Jewry in their midst. As the scholar Jonathan Hess of the University of North Carolina has noted, one “solution” popular among Enlightenment figures who harbored anti-Semitic feelings was to deport Jews to a colonial setting where they could be reformed. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, among the founders of German Idealism, noted in 1793 that the most effective protection Europeans could mount against the Jewish menace was to “conquer the holy land for them and send them all there.”

Indeed, Zionism crystallized as a political movement among European Jews explicitly to solve the problem of political anti-Semitism. For Zionist pioneers like Leo Pinsker and Theodor Herzl, anti-Semitism was an inevitable phenomenon that would occur at any time and place where Jews were a sizable minority. Normal relations with other nations could only be established by moving Jews to a place where they were a majority. Thus rather than pushing contemporary states and societies to devise new ways of accommodating difference, Zionist thinkers of Herzl’s generation ascribed to the logic that the Jewish “problem” could only be settled by removing Jews from European states.

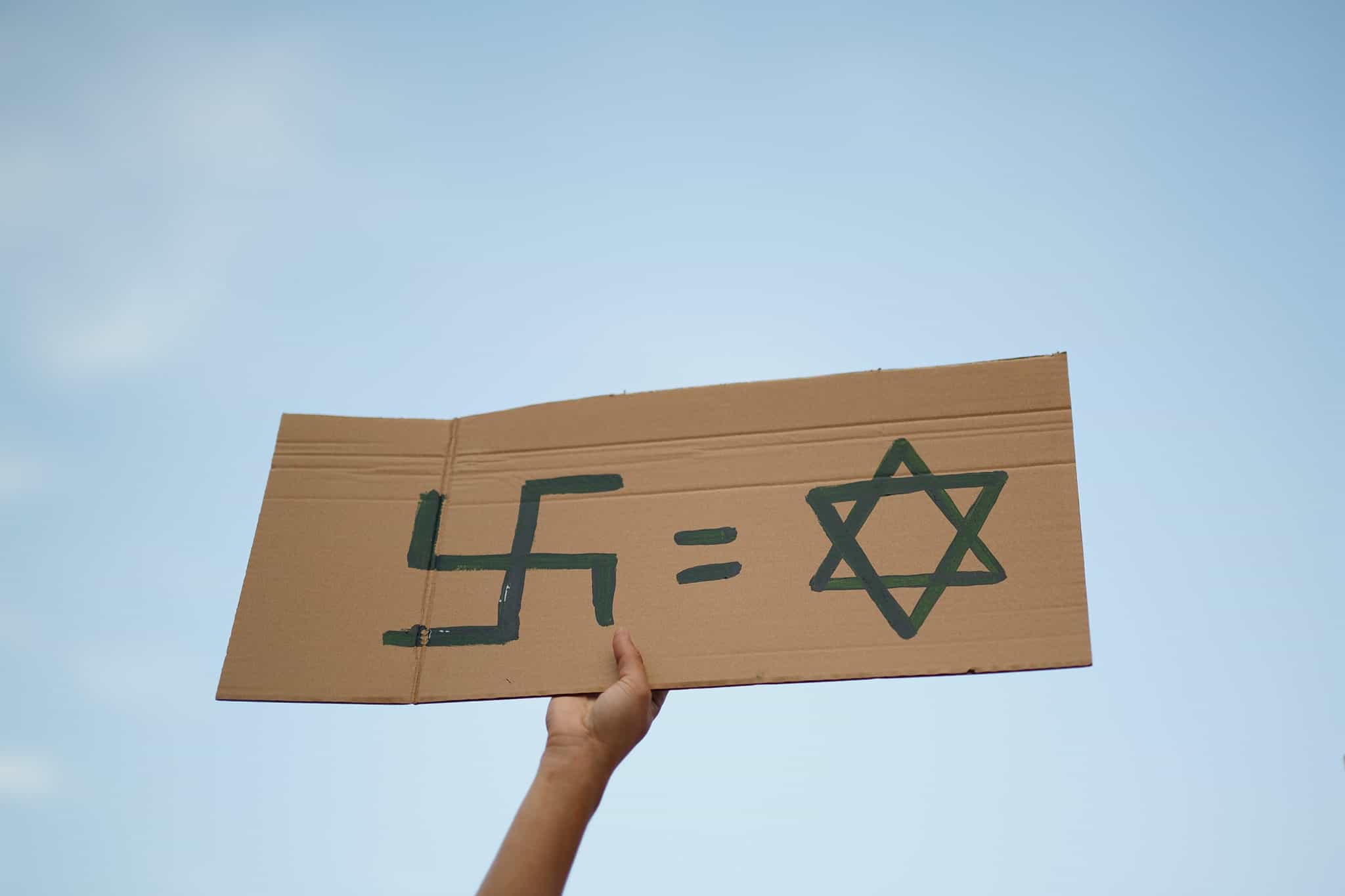

The idea that Jews belong not in their actual place of residence and origin, but in the Holy Land, was of course not a position that all Zionists ascribed to, either then or now. Yet it is not hard to see the very problematic logic that links such assertions to the sort of blood-and-soil nationalism that led to the destruction of European Jewish life. Nazism of course grew out of this context and insisted that Jews could never really be German. The Nazis, however, took this conclusion to a radically new place: it was ultimately extermination, rather than resettlement, that drove the Nazi position.

Though the scope of destruction was not yet known in the 1930’s and early 1940’s, many nevertheless find it astounding that there were attempts by right-wing Zionists during these years to establish ties with Nazi Germany. Numerous scholars have noted the fascist sympathies of certain members of the Revisionist Zionist camp, who bitterly feuded with mainstream Zionists and denounced them as Bolsheviks. The antipathy was apparently mutual, as David Ben-Gurion in 1933 published a work that described Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of the Revisionist movement, as treading in the footsteps of Hitler. The Zionist Right’s flirtation with fascism reached its tragic peak in 1941 when Lehi, Avraham Stern’s paramilitary splinter group, approached Otto Von Hentig, a German diplomat, to propose cooperation between the nationally rooted Hebraic movement in Palestine and the German state. Nazi Germany declined his generous offer, having stumbled across quite a different “solution” to the question of Jewish existence.

The answer must be a resounding “no.”

Jewish life flourishes in pluralistic societies within which difference is not a “problem” to be resolved, but a fact to be celebrated. The alliance of right-wing Zionists and the alt-right should not be viewed as an abnormality, but the meeting of quite compatible outlooks that assert — each in their own way—that the world will only be secure once we all retreat to our various plots of ancestral land. Nationalist thinking of this sort wrought more than its fair share of damage during the twentieth century. Let’s not enact a repeat performance in the twenty-first.

Suzanne Schneider is a historian of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Zionist movement, and a director and core faculty member at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.